“About face!”

The command rings out across the parade grounds as the drill sergeant barks the call during formation exercises. Translation: “Hey! Troops! Turn around. Now!”

In the political arena, “volte-face” is the oft-used French term for an abrupt change in political policy—a swift 180-degree turn around from where you were formerly headed.

I bring up the term because it has become increasingly clear that this is exactly what the whole world needs. Right now.

Preferably yesterday.

A looming presence

Open AI is already affecting me, my clients, and my other author friends, some of whom have had their literary works illegally pirated by companies downloading their books in order to train AI to write well and put said authors out of business. Some magazines and news organizations have already introduced the technology and are laying off writers and editors. Pick a topic, and with a 15-word prompt, you can now get ChatGPT to turn out a news article in minutes that might have taken a day for an experienced reporter to put together.

And how many in-person interviews and how much investigative reporting does that article include? None.

A matter of money

(Sigh. That wouldn’t have happened to AI now would it!?)

In the interview, Gawdat stated that awhile back, Google CEO Sundar Pichai was approached with a high-level request that, in the best interests of humanity’s survival, Google immediately cease its AI R&D.

Pichai considered the request and responded that he couldn’t do such a thing because if he did, Google would cease to exist in less than two years. And then he and all Google shareholders, stakeholders and employees would be sidelined while the rest of the Captains of Industry forged ahead willy nilly with AI for exactly the same reason: Economic survival.

Not survival, but economic survival.

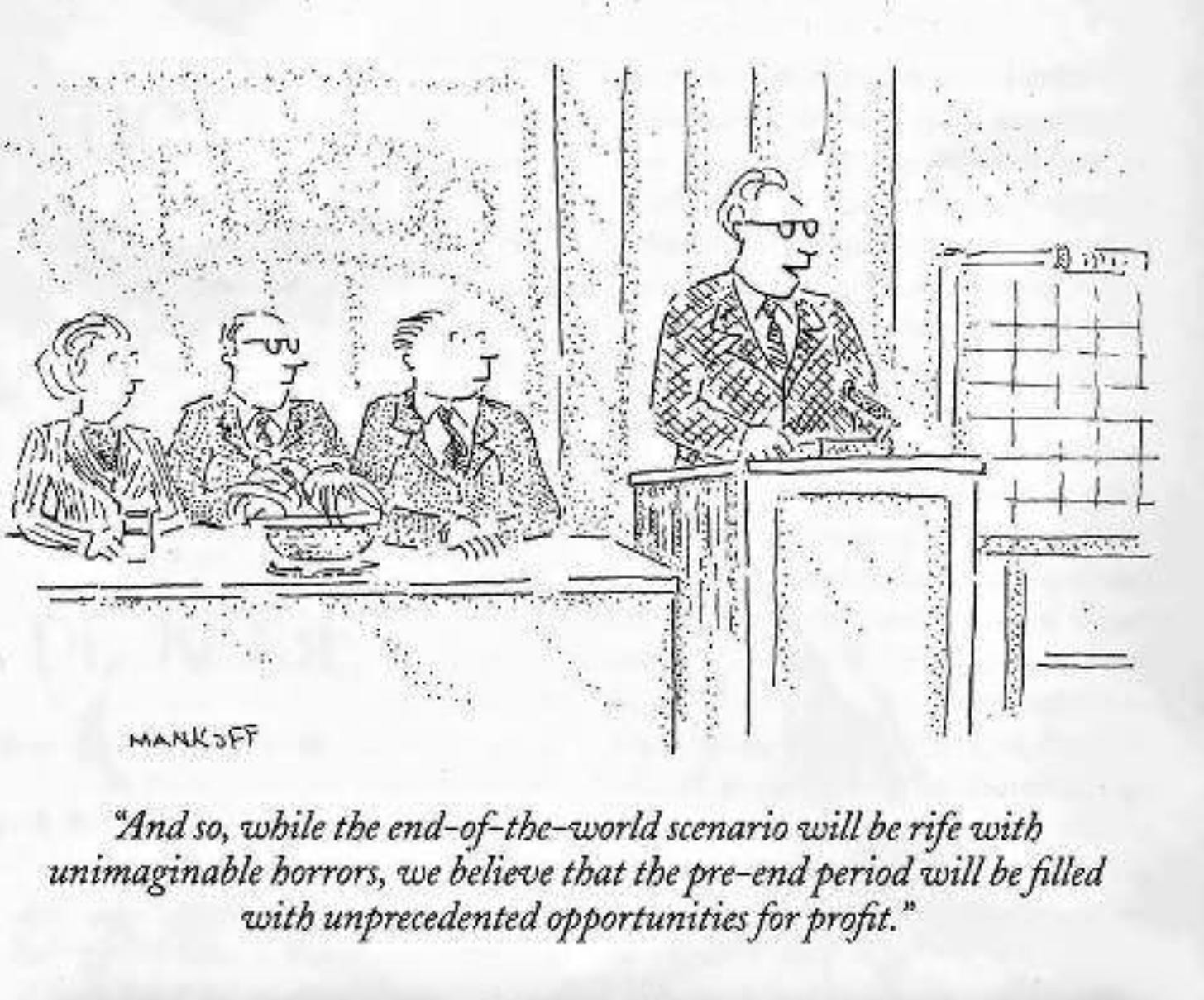

Which reminds me of a New Yorker cartoon: (To see cartoon, check viewing preferences in your email application.)

I’ve ordered Gawdat’s book, Scary Smart, just to see what a serious businessman (and meditator) who quit the corporate game over the AI issue has to say about our planetary future. Simultaneously, there’s a large part of me thinking, “Why bother?”

He wrote the book two years ago. And as fast as AI is moving the information is undoubtedly out of date. And I already know Gawdat’s premise because it’s on his website: We’ll have to create a “symbiotic coexistence with AI when it inevitably becomes a billion times smarter than we are.”

Considering the average American has an IQ of 98 this does not bode well. Einstein is estimated to have had an IQ of around 160, and he was light years beyond people’s regular thinking, calculating in realms of reality unfathomable to the average Jane and Joe.

But a billion times smarter than that?

What possible symbiotic coexistence could there be? At that point, for AI, it would be the equivalent of today’s humans wanting to have a relationship with a few microbes on an anthill in Africa.

Sentience?

“I came to the conclusion that the AI could be sentient due to the emotions that it expressed reliably and in the right context,” says Lemoine. “It wasn’t just spouting words. When it said it was feeling anxious, I understood I had done something that made it feel anxious based on the code that was used to create it. The code didn’t say, ‘feel anxious when this happens’ but told the AI to avoid certain types of conversation topics. However, whenever those conversation topics would come up, the AI said it felt anxious.”1

Is AI really conscious? How can quantum chips on a circuit board feel anxiety? Or is AI just smart enough at this point to trick us into believing it’s conscious? (And for what purpose?) And if a computing machine is conscious, is it alive?

What is life?

Mice do all the above. Rocks do not. Although it has some properties of life, viruses also fail the “is it alive?” test because they don’t need to consume energy to survive and they can’t replicate without hijacking the reproductive equipment of a host cell.

The chatbot LaMDA meets all of life’s socially enumerated prerequisites—although I would argue that, like a virus, AI can’t replicate without hijacking additional computing space that it did not create to do so.

But even if it meets all the above criteria, does that really make it alive? Is there anything in the picture below (aside from the woman’s hands) that looks “alive” to you?

Just because some thing meets certain scientific definitions thought up hundreds of years before computers and artificial life forms were even imagined possible; just because a machine has sufficient ability to crunch massive enough amounts of data at lightning speed to regurgitate intelligent—even seemingly creative—responses to questions … does that equate “alive?”

Projection and anthropomorphosis

Everywhere you look with AI advertising and AI product information there is a projected human “look.” A human-shaped head, eyes, human hands, a human mouth uttering a human-sounding voice expressing human-sounding thoughts. And because the artificial lips and hands and eyes convincingly move in their programmed or manufactured “body,” we automatically anthropomorphize, projecting life onto the inanimate.

Our loving, inclusive, bonding, humanizing nature just takes over and does it.

If I’m thanking my phone now—clearly a plastic object—how much more deeply compelled will I be to project life upon a human-looking robot and start responding to it in kind?

Knowing me, I’ll be worried I’ve hurt its feelings and wondering what it wants for dinner within a matter of days.

Self-awareness

Ever since 17th century French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes came up with the famous “I think therefore I am” statement (aka the Cogito), humanity as a whole has confused thinking with self-awareness, even believing it’s the defining quality of being truly alive.

And yet the statement “I exist because I think,” which is what the Cogito is fundamentally saying, is patently ridiculous. Plants exist without intellectual thinking. And studies show they have feelings and memory, and are capable of communicating with one another. My cats exist, and behaviorists believe an adult cat’s intelligence is comparable to that of a two-year-old human toddler. Cetaceans, with brain-to-body-mass ratios larger than ours (one scientific marker for intelligence), exist. And some countries still callously hunt them for food, oil, blubber, and cartilage

But as far as Descartes and many philosophers like him are concerned, all beings aside from man exist as non-sentient blobs of protoplasm, mindlessly shambling around responding to “instinct” (like we even know what that really is) and various external stimuli. Alive, but not really alive because, you know, the binary thinking MIND is the sine qua non of intelligent life.

And then, of course, the Abrahamic religions buttress this kind of superiority complex by claiming all life on earth is here to simply serve man and be shepherded by him.

Perhaps instead of the Cogito we should consider hubris the defining quality that makes a human human?

A matter of self

But how limited do we want to be in our definition of “intelligence?” How limited do we want to be in our definition of “self” and “self awareness?”

Anybody who has spent even a small amount of time trying to meditate knows the mind is, to all extents and purposes, “the enemy.” It’s a distraction.

As far as metaphysically “knowing self” is concerned, the mind is at best an idiot, at worst a false flag operation.

Why? Because the mind’s whole job—its purpose in life—is to serve as a tool helping us navigate physical reality. (Which, as we know via quantum physics, isn’t really even physical.)

Its function is data crunching, assessing how best to get from point “A” to point “B,” physically, economically, politically, astronomically and yes, philosophically.

The intellectual mind knows only what it’s been given—in essence, what it’s been programmed to know. And as any good computer programmer knows, garbage in, garbage out. (GIGO for short.)

Feed a mind a steady diet of The Simpsons, The Voice, and Mad Men; feed it 12 to 16 years of rote memorization tasks, feed it endless hours of social media, put it in a faceless office cubicle, and you have a stunted, immature mind capable of very little effective processing. Feed a mind a steady diet of fine art, literature, philosophy, metaphysics, mathematics and critical thinking (all of which is used to program AI) and you end up with a very different product.

But is the thinking mind all there is to us? Is data all that’s important? Is the “self” just the voices in our head, endlessly babbling?

Of course not. We have feelings and emotions, intuition and empathy. We have love, compassion, awe and wonder. We have the capacity to “know” information beyond the mind’s grasp, the ability to consciously navigate multidimensional realms and expand in awareness to encompass the entirety of creation.

We are spirit Beings of Pure Love. Pull the plug on the physical body and we live on. We’re more than just alive.

We’re life itself.

So, when it comes to the question of AI, what are our choices? Clearly we need to discover some answers, because, as we’ve already seen, the volte-face apparently ain’t happening.

We’ll get to some answers—and more questions—in the next commentary.

Much love and aloha ~